Norman Cross

RICHARD GUNN reveals the story of one of Peterborough’s lesser-known historical sites

Drive south from Yaxley, heading down the A15 towards the busy interchange with the modern A1, and amid the lush greenery of this rural part of Peterborough, something rather incongruous presents itself. Tucked off by the side of London Road, just before the A1 roundabout, is a stone column topped by a majestic bronze eagle,  now weathering to that bright, lurid green that all bronze monuments seem to adopt when exposed to the elements for any length of time. The busy or non-curious will speed past, oblivious. But if you’ve time to spare or are the type or person unable to resist a nose around places where something of significance has obviously happened in the past, it’s worth pulling over to investigate further.

now weathering to that bright, lurid green that all bronze monuments seem to adopt when exposed to the elements for any length of time. The busy or non-curious will speed past, oblivious. But if you’ve time to spare or are the type or person unable to resist a nose around places where something of significance has obviously happened in the past, it’s worth pulling over to investigate further.

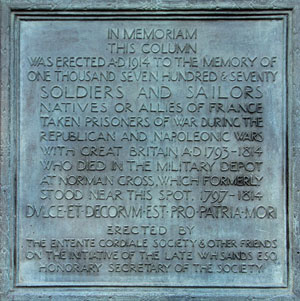

Fortunately, two plaques on the base of the column, plus a modern information board explain the reason behind this testimonial to the past. And it might come as quite a surprise to many. For within a stone’s throw of the eagle, in what is now a quiet field inhabited only by cattle, was once Norman Cross Prison Depot, the world’s first purpose-built prisoner-of-war camp.

Fortunately, two plaques on the base of the column, plus a modern information board explain the reason behind this testimonial to the past. And it might come as quite a surprise to many. For within a stone’s throw of the eagle, in what is now a quiet field inhabited only by cattle, was once Norman Cross Prison Depot, the world’s first purpose-built prisoner-of-war camp.

But the prison doesn’t date from the 20th century and one of the two wars against Germany, although the monument itself hails from the start of the First World War in 1914. The depot itself was disbanded almost a century ago previously, after the end of the Napoleonic Wars (known at the time as The Great War until the more widespread and destructive conflict of the 20th century stole that tragic crown). During the 17 years it was active, many thousands of foreign soldiers and sailors were incarcerated there, with a total of 1,770 losing their lives while captive. It is these fallen that the Norman Cross eagle chiefly commemorates.

Nothing now remains of the camp itself on the ground, although try Google Earth on a computer and the imprint of the original walls can still be seen in the 22-acre field, their bowed-out design echoed by the base of the memorial. The site remains a scheduled ancient monument however, and was recently visited by Channel 4’s Time Team, who carried out the first ever major archaeological excavation of Norman Cross. They uncovered hundreds of finds and some surprising facts as well.

“At its peak, the depot was home to more people than the neighbouring city of Peterborough, all squeezed into a much smaller area”

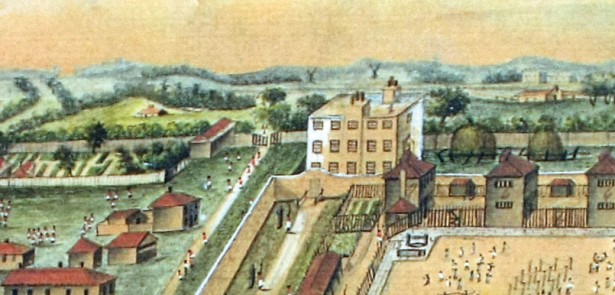

Not every building has disappeared though. Retrace your path up the A15 a bit and you’ll find the Norman Cross Gallery, a quiet little repository of fine art. It’s housed in one of the former stable blocks of the depot, next door to the imposing Agent’s House. Both are now owned by Derek Lopez and his wife Mary, with Derek also the chairman of The Friends of Norman Cross, the historical society established to promote interest in this intriguing part of Cambridgeshire. An art gallery seems a complete contrast to the location’s former use, but there is an obtuse link; for during the years of the camp, prisoners would earn extra money for themselves by making models out of bone and wood to sell to local residents and on the prison market. Some of these intricate and exquisite pieces of art can be seen on display in the gallery, as well as at Peterborough Museum in the city centre. Nowadays though, the other works that appear in the gallery are produced under more fortunate circumstances.

Norman Cross is chosen

The need for a prison at Norman Cross arose due to Britain’s constant conflicts with France during the closing years of the 18th century and the opening of the 19th. From 1793 until 1815, around 200,000 captured soldiers and sailors were brought to the UK and incarcerated in locations such as Portchester Castle near Portsmouth or the notorious ‘hulks’, mouldering old ex-warships too worn out for combat. Conditions in the hulks were especially atrocious. The government started searching for new places to house those captured and, in 1796, decided on Norman Cross. The site, which would be run by the Navy, despite its inland location, had many advantages. It was close to the Great North Road from London (the present A1) and also convenient for the ports of Yarmouth and King’s Lynn, so internees could be shipped in, although they could also be brought by river to Peterborough, Stanground or Yaxley. Nearby Peterborough also provided a ready supply of manpower and resources, while the surrounding fertile farmland provided food.

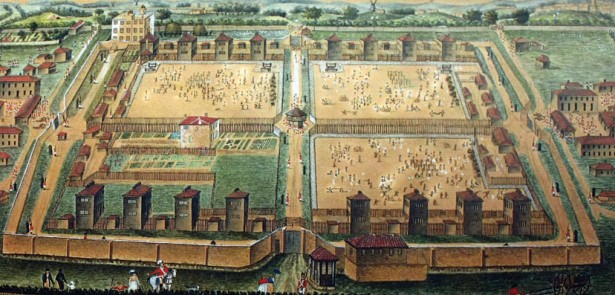

Construction took about four months, from December 1796, with 500 carpenters and labourers constantly employed. The hurriedly-prepared site was almost completely made from wood (although a stone exterior wall was added in 1805, due to too many escapes), and accepted its first prisoners in April 1796. The total cost came to £34,581 11s and 3d, a small fortune at the time. The layout was four quadrangles, grouped around a central blocktower, in which cannons were mounted, with further guard towers around the perimeter. Up to 7,000 captives could be housed, along with 500 soldiers to guard them all; at its peak, the depot was home to more people than neighbouring Peterborough, all squeezed into a much smaller area. Accommodation for those incarcerated consisted of 22-feet by 100-feet prison buildings into which 500 men would be crammed, sleeping in hammocks. It wasn’t just British and French inhabitants either; the Napoleonic Wars enveloped the whole of Europe, with the result that Norman Cross also saw ‘residents’ from Holland, Spain, Italy, Germany and Africa. Women, and children as young as 12, were also to be found at the depot, and alongside the military PoWs, the British also used the camp for civilians captured on merchant navy vessels as well as foreign government officers.

Conditions, initially at least, were reasonable for the era and certainly far more habitable and hygienic than on the prison hulks. Captives were educated in languages, dancing, mathematics and navigation, and were also encouraged to make models from bone and wood which they could then sell. With so many of the inmates from Republican France, miniature working guillotines proved unsurprisingly popular! The authorities reasoned that the more those at Norman Cross had to do with their hands and minds, the less time they could spend on planning escapes. Nevertheless, there were breakouts; on three occasions, 16 men at a time escaped, and tunnels were also discovered. Insubordination grew so rife at one point that soldiers had to be brought in from Shropshire to bolster the local Peterborough militia and volunteers.

As the numbers inside increased, so conditions deteriorated for them. A British soldier recorded those he had to guard as ‘cooped up in that place and clothed in yellow (the prison dress), to expiate their revolutionary sins by many years captivity and exile in loathsome prison, cut off from family and friends.’ He also wrote that ‘their necessities forced them to exert their ingenuity in making various curious toys which they disposed of at a very low rate to enable them to procure a few comforts to alleviate their extreme wretchedness… for want of clothes many of them suffered every privation rather than be clad in a conspicuous and humiliating colour.’

The British blamed the French for the clothing problem; it was common practice that enemy governments paid for their PoWs to be clothed, something the British supposedly did with all its soldiers and sailors captured by the French. Many of those at Norman Cross sold their clothes to finance their gambling habits. When some men – presumably those who were especially bad at gaming – were found completely naked, the Lords of the Admiralty instructed that all captives be clothed at once, whether or not the French coughed up the cash or sent supplies. Some of the more resourceful inmates also turned to forgery, a crime punishable by death if discovered. In December 1804, engraved plates and printing implements of a very high standard were found during one search.

Disease and suicide

But the worst problem those at Norman Cross had to contend with was disease. With so much humanity in such little space, epidemics were common. Smallpox, typhus, measles, consumption and dysentery all ravaged the camp, striking down both those inside and outside the walls. Of the 1,770 prisoners recorded as having died at Norman Cross, 1,021 alone died during 1800 to 1801 during an outbreak of typhus. And as well as death by disease or for crimes and escape attempts, some inmates also took their own lives, unable to bear the harsh conditions of the camp.

Hostilities came to an end in 1814, with Napoleon defeated. Guards, captives and locals all celebrated together; by June, nearly all the PoWs had gone. Just one solitary soul remained, Petronio Lambertini, of the Italian Regiment of the French Army. He was too ill, from consumption, to be moved and subsequently died a few months after his comrades had left. Thus he became the last prisoner to be buried at Norman Cross. The following year, the prison was put up for auction and completely dismantled, save for some auxiliary buildings such as the wooden Agent’s House, which was strengthened by brick and passed into private hands. Most of the rest of the camp was recycled for building materials. Gradually the site of Norman Cross reverted back to nature; its position marked only by what few altered structures remained, some scattered wells and parts of the perimeter wall. Even the location of the graves of those who died there became lost.

Interest in the prison was revived almost a century later by Dr Thomas James Walker, an eminent surgeon at Peterborough Infirmary (now the city’s museum building). He was also a keen historian and archaeologist, responsible for books on Roman and Anglo-Saxon Peterborough. In 1913, he published the snappily-titled The Depot for Prisoners-of-War at Norman Cross, Huntingdonshire, 1796 to 1816 which re-focussed attention on what was now a sleepy and forgotten part of rural Peterborough. The year after the book appeared, the Entente Cordiale Society and the Peterborough Natural History, Scientific and Archaeological Society (of which Walker was a past president) erected the eagle monument to mark the centenary of the camp’s closure, as well as remember all those who perished there. Even more might have been written on the depot, had not Walker died in 1916; the British Medical Journal noting in his obituary that ‘a second edition was quickly called for, and the work is recognised as the standard authority on a little-known subject’. The eagle became a familiar landmark for travellers on the west side of the Great North Road, until it was moved adjacent to the field where the depot had once stood when the A1(M) was widened.

All went quiet again until, one night in autumn 1990, locals awoke to find the monument column toppled and the bronze eagle stolen. It has never been recovered, neither were the perpetrators ever found; it seems likely it was sold for its scrap value. But curiosity in the Napoleonic history of Norman Cross was once again sparked, and an appeal launched to raise the funds to restore the monument as well as promote awareness of the site’s significance. Although the column itself was soon re-erected, the bronze eagle took somewhat longer to appear. In the meantime, Peterborough Museum continued to keep the camp on the local radar by launching the Norman Cross Conservation Project in 2002, to care for its extensive catalogue of prisoner-of-war sculptures, models and toys, many of which had started to deteriorate. The collection now has a large, dedicated room on the museum’s top floor.

In 2004, enough funds had been raised to resurrect the bronze eagle; sculptor John Doubleday – also responsible for the statue of Sherlock Holmes on Baker Street – was commissioned to create a replacement. It was unveiled, before a crowd of over a thousand, on April 5, 2005 by the Duke of Wellington. His ancestor, the first Duke of Wellington, had been somewhat responsible for so many of Norman Cross’ inhabitants during the Napoleonic Wars of course. In October of that year, a heritage trail was unveiled to coincide with the Trafalgar bicentenary celebrations.

The story of the Norman Cross Prison Depot was brought fully up-to-date by the visit of Time Team in July 2009, for a programme broadcast in October 2010. For three days, the squad of 50 archaeologists, researchers and production crew, fronted by Tony Robinson, excavated the site. Their trenches revealed carved items made from bone, as well as pottery, buttons, glass, knife handles, parts of the prison itself and quite a few dominoes, presumably used for gambling.

The Time Team crew also found two of the lost cemeteries, one for the British guards and the other for prisoners, immediately to the north east of where the camp stood. Supposedly a small burial ground, surveys revealed the likelihood of hundreds, possibly even thousands of other graves nearby. A dig also took place on the other side of the A1, in a farmer’s field that records showed had been purchased by the government to use as a cemetery. However, no bodies were found. The programme concluded that most of the captives who died were laid to rest in the other location discovered, adjacent to the depot.

The Time Team crew also found two of the lost cemeteries, one for the British guards and the other for prisoners, immediately to the north east of where the camp stood. Supposedly a small burial ground, surveys revealed the likelihood of hundreds, possibly even thousands of other graves nearby. A dig also took place on the other side of the A1, in a farmer’s field that records showed had been purchased by the government to use as a cemetery. However, no bodies were found. The programme concluded that most of the captives who died were laid to rest in the other location discovered, adjacent to the depot.

“The site has proved to be much more important and spectacular than we originally thought,” said Peterborough Museum archaeologist Ben Robinson about the Time Team excavation. “Norman Cross is such an important site in modern world history, and yet there are still so many mysteries about it.”

Who knows what secrets are still left to be uncovered…?