Cromwell’s Huntingdon

Oliver Cromwell was born in Huntingdon on 25 April 1599 – 425 years ago this year. He lived in the town for over half his life and went to school in the building which is now the Cromwell Museum. The Museum’s new exhibit, opening on 4 May, looks at what Huntingdon was like at that time, and the impact that it had on its most famous resident.

Seventeenth century Huntingdon’s narrow high street was one of the busiest roads in England, the Great North Road between London and York. A journey between these two cities took four or five days by horseback or carriage, so many travellers broke their journey for a meal, change of horses or a night’s sleep in one of the many taverns in the town. It was also Huntingdonshire’s county town and held twice-weekly markets, as it still does today. The river had been navigable for trading ships in the Middle Ages; changes to its course to create dams and mill ponds upstream made this more difficult, but heavy goods were still brought to Huntingdon by smaller boats.

Everywhere was much smaller than today in the seventeenth century – more people live in London in 2024 than did in the whole of England and Wales in 1600. Based on surviving tax records, Huntingdon was a small market town, numbering less than a thousand people in Cromwell’s time. Most houses were built of timber with thatched roofs, many having just a single storey. Many shops had narrow frontages but extended back a long way, to provide living accommodation behind the shop. The loudest sound in the town would have been church bells. At night there was no street lighting other than lanterns, which taverns were required to have to light their doorways.

Huntingdon had four parish churches at the time Cromwell was born in 1599. Due to the declining population only three of these were left by the 1660s, only two of which remain today. Religion was the centre of many people’s lives, particularly in a time when there was division over the future direction of the church. Several notable Puritans preached locally by 1630, including Walter Welles in Godmanchester and Job Tookey in St Ives.

Huntingdon had four parish churches at the time Cromwell was born in 1599. Due to the declining population only three of these were left by the 1660s, only two of which remain today. Religion was the centre of many people’s lives, particularly in a time when there was division over the future direction of the church. Several notable Puritans preached locally by 1630, including Walter Welles in Godmanchester and Job Tookey in St Ives.

The surrounding landscape was very different to that of today. To the west was rich agricultural land, where most of the population locally would have made their living farming. To the east was fen and marshland, which was starting to be drained. In 1630 the Earl of Bedford and a group of wealthy investors (or ‘Adventurers’) were licensed by King Charles I to drain the Fens, creating new agricultural land and reducing flooding. They hired a Dutch engineer, Cornelius Vermuyden, to design and carry out the works. Many local people were opposed to the scheme, as it threatened their traditional livelihoods including fowling, fishing and reed cutting. Some of them, nicknamed “Fen Tigers”, attacked the works, filling in drains and destroying equipment.

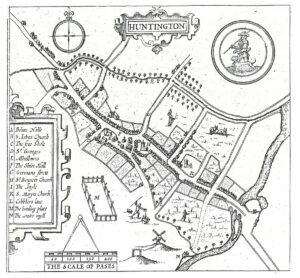

Accurate maps that we might recognise today were still in their infancy. Many in the early 1600s were produced by the Cheshire cartographer John Speed, whose county maps gave some detail of places across England, although only major roads and rivers were marked. On each county map, plans of the county town and local cathedral city were included, such as one of Huntingdon. It was drawn in 1610, the same year that Oliver Cromwell came to school here. Speed drew maps like these in a day and they seem to have been surprisingly accurate.

Royal Visitors – Alive and Dead!

Given Huntingdon’s position on the Great North Road and as a county town, royal visitors were known throughout its history. They became very common during the early 1600s, when a local mansion nearly became a royal palace.

James I came to Huntingdon on his way south to London in 1603, on the way to his coronation. He stayed at Hinchingbrooke House on 27th April, where he was richly entertained with the local community by Cromwell’s uncle Oliver at great expense, including gifts of a gold cup, hawks, horses, and hounds. The investment paid off: Sir Oliver was knighted and made a gentleman of the Privy Chamber.

Unfortunately for the Cromwells, James I enjoyed his visit to Hinchingbrooke so much that he became a regular visitor, staying at least 15 times during his reign, perhaps more than anywhere outside of London. The King did not pay his way on such visits and expected lavish treatment. His sizeable entourage also had to be accommodated in Huntingdon. The cost almost bankrupted the Cromwell family, Sir Oliver trying to clear the debt by selling Hinchingbrooke to the crown as a royal hunting lodge. A Royal Wardrobe (store of clothes and equipment) was kept at Hinchingbrooke by 1625, but the deal fell through when James died. Sir Oliver Cromwell was left with a substantial debt. He cleared this in 1627 by selling Hinchingbrooke to Sidney Montague, whose family (later the Earls of Sandwich) owned the house until 1962. Sir Oliver moved to his other residence at Ramsey.

James I’s mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, had a post-mortem visit to Huntingdon in 1612, when her coffin was transported from Peterborough Cathedral to Westminster Abbey. Queen Mary had been imprisoned at Fotheringhay Castle in 1586, accused of treason. She was found guilty of being involved in the Babington Plot to depose her cousin Queen Elizabeth I of England and was executed on 7th February 1587. Her body was sealed in a lead coffin and locked in a room at Fotheringhay for the next five months. On 1st August 1587 she was buried with a regal funeral at Peterborough Cathedral.

On 1 October 1612 the Dean of Peterborough received a letter from James I, ordering him to “deliver the corpse of our dearest mother… being taken up, in as decent and respectful a manner as is fitting…” The body was taken to London, a four-day journey. On the first night, the cortege arrived in Huntingdon and the Queen’s coffin rested overnight in All Saints’ Church. Oliver Cromwell would have been a 13-year-old pupil at the grammar school at the time. Did he sneak across to have a look at the coffin of a beheaded Stuart monarch? Did this set a pattern for the future?

On 1 October 1612 the Dean of Peterborough received a letter from James I, ordering him to “deliver the corpse of our dearest mother… being taken up, in as decent and respectful a manner as is fitting…” The body was taken to London, a four-day journey. On the first night, the cortege arrived in Huntingdon and the Queen’s coffin rested overnight in All Saints’ Church. Oliver Cromwell would have been a 13-year-old pupil at the grammar school at the time. Did he sneak across to have a look at the coffin of a beheaded Stuart monarch? Did this set a pattern for the future?

The future Charles I visited Huntingdon on at least two occasions, as a boy accompanying his father on some of his frequent stays at Hinchingbrooke House. These visits may have given rise to the legend of him playing in the garden with the young Oliver Cromwell, resulting in a fight, which Cromwell won. These stories emerged much later and seem unlikely given the etiquette that would have been involved protecting a royal prince.

The Cromwell Family

Richard Cromwell (born Richard Williams) was the nephew of Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s Chief Minister. When his uncle fell from power in 1540 and was executed, Richard remained at court, fought in France, and was knighted by the King. He was granted former monastic property in and around Huntingdon, Sawtry, Ramsey and St Neots, including the former nunnery at Hinchingbrooke. From 1538 it began to be converted into the grand house that we can still see today.

The estate was inherited by his son, Henry Cromwell, in 1544. Henry continued to improve Hinchingbrooke and hosted Queen Elizabeth I there as a guest in 1564, after which he was knighted.

Up until the 1620s, the Cromwells were the wealthiest and most important family in the area, serving as High Sheriffs, Justices of the Peace and Members of Parliament. Their financial problems after this time led to them becoming less prominent.

Oliver Cromwell’s early life

There are many stories about Oliver Cromwell’s childhood; in reality we know very little about it. Many legends, such as that of him being kidnapped by his uncle’s pet monkey and carried up onto the roof of Hinchingbrooke House date from later centuries.

Huntingdon’s parish register records his birth and christening on 25 April 1599. His father, Robert, was the second son of Sir Henry Cromwell. Robert lived in a house at the end of Huntingdon high street, converted from a former friary, with his wife Elizabeth, his six daughters and one son – Oliver. The family earned their living from the rents of several properties in the town. We know little about Oliver’s upbringing other than that he attended the Huntingdon Grammar School (situated in the building that is now the Museum) between 1610 and 1616.

After a year studying at Sidney Sussex College in Cambridge, Cromwell returned to Huntingdon in 1617 on the death of his father. He was now responsible for his mother and six sisters.

In 1620 Cromwell married Elizabeth Bourchier, and they settled at the house on Huntingdon High Street, where over the next decade they had six children. Together with Cromwell’s mother and those of his sisters yet to be married, it must have been a very busy household.

In 1628 Cromwell was seen by the Swiss doctor Theodore Mayerne in London and diagnosed with ‘melancholia’, which may be interpreted to be depression, which he had periodic bouts of throughout his life. This may have been triggered by his financial problems. He was also treated for physical symptoms including a skin condition and various pains, which may have been related to his mental state.

In 1628 Cromwell was seen by the Swiss doctor Theodore Mayerne in London and diagnosed with ‘melancholia’, which may be interpreted to be depression, which he had periodic bouts of throughout his life. This may have been triggered by his financial problems. He was also treated for physical symptoms including a skin condition and various pains, which may have been related to his mental state.

Cromwell’s father and uncles had been MPs for Huntingdon in parliaments called during the reigns of Elizabeth and James I. Cromwell himself was elected as MP for the town in the Parliament of 1628-29. He only made one poorly received speech, on a matter of religious policy, in the parliament that was dismissed by Charles I, who then ruled for the next 11 years without one.

The Cromwell family remained in Huntingdon until 1631 when they sold their property and moved to St Ives, where Cromwell became a tenant farmer. The move was partly prompted by a decline in his finances, caused by having to sell off property to finance his sisters’ dowries (a financial settlement as part of a marriage contract) and a decline in the value of his remaining property.

Huntingdon was also divided by political controversy. In 1625 a wealthy merchant, Richard Fishbourne, left £2,000 (worth about £300,000 today) to the town. Some local people felt this should be used for charity to the poor; others like Cromwell’s schoolmaster Thomas Beard, felt it should be used to fund a lectureship. The argument took six years to resolve with a lectureship created, but it caused such animosities between burgesses that violence regularly ensued at local elections.

This caused some burgesses to petition King Charles for a new charter, which replaced regular elections with a governing body of a mayor and a small group of aldermen who were appointed for life. Cromwell objected to this – possibly as much as he was not included in this group – and was so intemperate in his language that he was imprisoned for five days and forced to make a humiliating public apology. Battling with depression, financial problems and local politics, Cromwell moved from Huntingdon to St Ives in May 1631.

Impact on Cromwell?

Oliver Cromwell was born and educated in Huntingdon, spending over half his life in this, his home-town. Many of his children were born and baptised here. Growing up in a household with many women seems to have had a great impact on him; from his surviving correspondence he was more comfortable confiding in women than men.

This was where Cromwell gained his first political experience, not always successfully, in local politics and as an MP. It is significant too, that when Civil War erupted in 1642 it was to Huntingdon that Cromwell returned to raise his first soldiers to fight for Parliament. Aside from Westminster and the battlefield – it was Huntingdon that most made Oliver Cromwell…

- You can discover more about this by visiting the ‘Cromwell’s Huntingdon’ exhibit at the Museum until 29 September 2024. For more details and opening times visit: www.cromwellmuseum.org.