The ‘Weaker Vessel’?

A new exhibit at the Cromwell Museum in Huntingdon looks at the experience of women through the Civil War period – when the ‘world was turned upside down’ – including members of Oliver Cromwell’s own family...

In the deeply religious 17th century, the biblical phrase ‘weaker vessel’ to refer to women would have been very familiar. In the popular imagination today the role of women during the Civil Wars has been limited to that of aristocratic ladies defending their husbands’ estates, or women camp-followers with armies.

Whilst it is true that these roles did exist, and that generally women lacked the rights and equality that we aspire to today, that is not to say that they did not find the opportunity to take part in the tumultuous events of the 1640s. The upheaval of Civil War, Revolution and a Republic provided opportunities for women to act as spies, pamphleteers, preachers and even soldiers.

Whilst it is true that these roles did exist, and that generally women lacked the rights and equality that we aspire to today, that is not to say that they did not find the opportunity to take part in the tumultuous events of the 1640s. The upheaval of Civil War, Revolution and a Republic provided opportunities for women to act as spies, pamphleteers, preachers and even soldiers.

The impact of the Civil Wars on families and communities in Britain and Ireland cannot be underestimated; around 8% of the population (20% in Ireland) died in the fighting or war-related disease, a greater proportion than any other conflict in our history. With up to a third of men away fighting, many women found themselves running their households, families and even businesses by themselves. They coped with food shortages, rising taxes, and having soldiers billeted on their households as armies passed through their community. Looting, theft, and rape was not uncommon. We get some of these human stories from the Civil War Petitions Project, looking at the applications for military pensions provided by Parliament in the 1650s for wounded soldiers, widows, and orphans. The diary of a Royalist diplomat, Ann Fanshawe, shows how she visited her husband in prison, nursed him when he fell sick, and raised money needed to keep the family solvent.

In the male dominated 1600s, women were often dismissed from men’s minds as being incapable of espionage. Ironically this made them ideal spies, and there are examples of women who worked for either side. Lady Jane Whorwood acted as a secret messenger for King Charles whilst he was imprisoned by Parliament and twice tried to help him escape; Elizabeth Atkins, also known as ‘Parliamentarian Joan’, worked in taverns as an informant, discovering secret caches of weaponry ready to be smuggled to Royalist troops.

In the male dominated 1600s, women were often dismissed from men’s minds as being incapable of espionage. Ironically this made them ideal spies, and there are examples of women who worked for either side. Lady Jane Whorwood acted as a secret messenger for King Charles whilst he was imprisoned by Parliament and twice tried to help him escape; Elizabeth Atkins, also known as ‘Parliamentarian Joan’, worked in taverns as an informant, discovering secret caches of weaponry ready to be smuggled to Royalist troops.

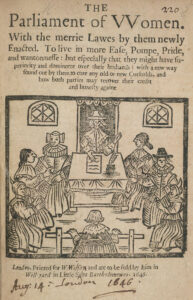

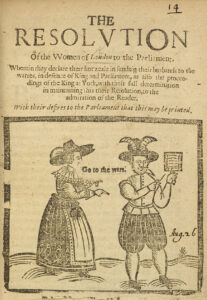

Radical political groups such as the Levellers suggested in the 1640s that for the first time all men should have the vote, although there was no suggestion that this should be extended to women. Several women still became prominent Levellers, including Mary Overton, Elizabeth Lilburne, and most particularly Katherine Chidley, who was a lay preacher, campaigner, and pamphleteer. In April 1649 Chidley and hundreds of other women gathered at Parliament in a protest march, demanding the release of John Lilburne and other Leveller leaders. Their petition was rejected by MPs, “they being women and many of them wives, so that the Law took no notice of them.”

Women also fought in the wars: Dorothy Hazard lead a group of women to barricade breaches in the walls of Bristol during the Royalist assault in 1643, whilst Lady Mary Bankes defiantly held off Parliamentarians besieging Corfe Castle three times. Even Queen Henrietta Maria styled herself the ‘She-Generalissima’ during her march from Bridlington with reinforcements for King Charles at Oxford.

Not only did women take part in military actions openly, recent research also suggests that some disguised themselves as men to fight. A few such women became famed in pamphlets such as the crossdressing highwaywomen Mary Firth, also known as ‘Moll Cutpurse’. Others were wives, unmarried partners, would-be female soldiers and even prostitutes motivated by a desire to fight or to remain close to their partners, such as Anne Dymocke from Lincolnshire, who in 1655 disguised herself as a man to remain with her lover, John Evison. In a draft set of

Not only did women take part in military actions openly, recent research also suggests that some disguised themselves as men to fight. A few such women became famed in pamphlets such as the crossdressing highwaywomen Mary Firth, also known as ‘Moll Cutpurse’. Others were wives, unmarried partners, would-be female soldiers and even prostitutes motivated by a desire to fight or to remain close to their partners, such as Anne Dymocke from Lincolnshire, who in 1655 disguised herself as a man to remain with her lover, John Evison. In a draft set of

regulations for the Royalist forces in 1643 King Charles ordered that “no woman presume to counterfeit her sex by wearing man’s apparel under pain of the severest punishment”. Although never published, this suggests the king believed that female crossdressing was widespread in his army.

Some also found their situation elevated because of the upheavals. Prior to the Civil Wars, Elizabeth Cromwell was a middle-class Cambridgeshire housewife, living with her family at their house in Ely. In the 1650s she found herself as ‘Her Highness the Lady Protectoress’, effectively a republican First Lady as her husband Oliver became head of state. After his death she retired into obscurity at Northborough, near Peterborough, where she died in 1665 and was buried in the parish church.

To find out more about these and other stories, visit ‘The Weaker Vessel? Women of the Civil Wars’ exhibit that runs from 2 December 2023 to 7 April 2024. It is open during Cromwell Museum opening hours – 11am-3.30pm Tuesday to Friday, 11am-4pm Saturdays and Sundays. Admission is free of charge. For more details see cromwellmuseum.org.