Remote Places

Remote Places 1 2

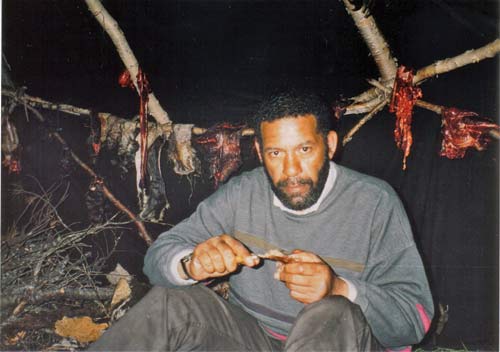

As a traveller, of course, you don’t spend all your time eating or dealing with the consequences. There’s something deeper lurking behind these questions, and it’s the most basic of all. It’s also the hardest to answer. Why do it? Why travel, often alone, in remote places where unpronounceable diseases are commonplace and discomfort almost guaranteed?

As a traveller, of course, you don’t spend all your time eating or dealing with the consequences. There’s something deeper lurking behind these questions, and it’s the most basic of all. It’s also the hardest to answer. Why do it? Why travel, often alone, in remote places where unpronounceable diseases are commonplace and discomfort almost guaranteed?

Different people claim different motives, of course. Some insist that they travel in order to spread peace and harmony amongst the nations. No doubt they believe this, though it’s never been one of my ambitions. In the mid-1980s I travelled to Beirut in the middle of the Lebanese civil war, after a friend there had misleadingly assured me that it wasn’t that dangerous. It turned out to be very dangerous indeed. Far from wishing to reconcile the warring factions, I found all my efforts were simply devoted to ensuring that I got out with a whole skin. I devoted no time or energy to anything or anyone else.

Others claim worthy ecological motives. They travel to the Arctic so that they can assess for themselves the impact of global warming. They trek through rainforests to monitor the presence of loggers or to count tree-frogs. I respect these motives, but they weren’t the ones which persuaded me to travel in Baffin Island and Greenland – and I’ve always found travelling in forest so hard that the last thing on my mind was stopping to count anything. And if I’m truthful, I can get a little weary of the ecological angle. For one thing, it sometimes seems that every single piece of weather is the consequence of global warming. We’re often told that the Arctic is melting faster than ever before, and no doubt this is true. But when I found that I couldn’t land on Ellesmere Island because of unusually heavy pack-ice, I was told that this too was due to increased temperatures, though I found no one who could explain exactly how. It is dispiriting, I’ll agree, to see large swathes of the Amazon turned into cattle-ranches and soya plantations. When I first went to Manaus, the forest started just beyond the outskirts of the town: now you have to drive for hours before you reach it. But I’m not sure that people from Europe, which cut down almost all its forest centuries ago, are in a very good position to tell Brazilians that they mustn’t. And I can’t always feel personally responsible.

Others claim worthy ecological motives. They travel to the Arctic so that they can assess for themselves the impact of global warming. They trek through rainforests to monitor the presence of loggers or to count tree-frogs. I respect these motives, but they weren’t the ones which persuaded me to travel in Baffin Island and Greenland – and I’ve always found travelling in forest so hard that the last thing on my mind was stopping to count anything. And if I’m truthful, I can get a little weary of the ecological angle. For one thing, it sometimes seems that every single piece of weather is the consequence of global warming. We’re often told that the Arctic is melting faster than ever before, and no doubt this is true. But when I found that I couldn’t land on Ellesmere Island because of unusually heavy pack-ice, I was told that this too was due to increased temperatures, though I found no one who could explain exactly how. It is dispiriting, I’ll agree, to see large swathes of the Amazon turned into cattle-ranches and soya plantations. When I first went to Manaus, the forest started just beyond the outskirts of the town: now you have to drive for hours before you reach it. But I’m not sure that people from Europe, which cut down almost all its forest centuries ago, are in a very good position to tell Brazilians that they mustn’t. And I can’t always feel personally responsible.

I fear my own motives must seem very frivolous. I just like seeing things which are very different. By frivolous, I don’t mean that I don’t do a fair amount of reading – I don’t think I could call it research – before going anywhere. I just mean I go to places that I think will be interesting. I’m moderately interested in wildlife: I’ve seen polar bears in the Arctic; snow leopards in Mongolia and most of the larger African animals – but I have to admit that I’m never interested in them for very long. This is mainly because they’re usually too far away or difficult to keep in view for more than a few minutes at a time. There are still some animals I’d like to see and haven’t; despite two visits to India, I’ve never seen a tiger, and last year I managed to miss seeing grizzly bears on the Atnarko River in British Columbia, despite spending all day there and having one cross the road on my way in. So perhaps it’s fortunate that I don’t generally travel in order to see animals.

I’m most attracted by landscapes, and the people who live in them. I recently travelled to the O mo Valley in south-west Ethiopia It’s a hot but beautiful area, containing a variety of ethnic groups {or tribes, as we used to call them). These include the Mursi, who live not far from Lake Turkana. Like most of the people in the area, they’re primarily cattle-herders. The men are famous for their sometimes lethal stick-fights; the women for wearing lip-plates. I should think that twenty years ago you could have persuaded yourself quite easily that this was Africa’s last Eden. But things have changed. Decades of war and revolution throughout Ethiopia have flooded the Omo with guns; you’re far more likely to see people with AK47s than with spears nowadays.

mo Valley in south-west Ethiopia It’s a hot but beautiful area, containing a variety of ethnic groups {or tribes, as we used to call them). These include the Mursi, who live not far from Lake Turkana. Like most of the people in the area, they’re primarily cattle-herders. The men are famous for their sometimes lethal stick-fights; the women for wearing lip-plates. I should think that twenty years ago you could have persuaded yourself quite easily that this was Africa’s last Eden. But things have changed. Decades of war and revolution throughout Ethiopia have flooded the Omo with guns; you’re far more likely to see people with AK47s than with spears nowadays.

Since the mid-1990s, the area is well on the tourist trail; outsiders are no longer a novelty, and I knew before I left home that there would be no chance whatever of taking a photograph without paying for it. It’s still possible to see women wearing goatskin robes, or men with ostrich-feather plumes in their hair – but you’re quite as likely to see people in cheap Italian football shirts, and when I managed to attend a wedding ceremony in the Hamar tribe, the women wore heavy bras of the sort that haven’t been seen in Europe since 1960. And yet, despite all the concessions to modernity, it was still thrillingly different. At the wedding, for example, the naked bridegroom jumped over a line of bulls. No matter that the cattle pen also contained a high-powered motorcycle. I don’t demand that people be kept like wild animals in human reservations, immune to any kind of change. I’m just happy if things aren’t the same as home.

One other question I do get asked a lot, is why I travel alone. I don’t always do so, but I must admit I  prefer it. A few years ago I rather lazily signed up for a tour along the upper reaches of the Amazon. I should have simply hired a boat and a guide and done it on my own. For one thing, since it was August, most of my companions turned out to be teachers from Britain. We cruised through the flooded forest, catching occasional glimpses of giant otters and river dolphins: it should have been magical. But being teachers (and, before anyone writes in, I used to be one myself) they found it impossible not to talk shop, so that our voyage was accompanied by non-stop discussion of Key Stage 3 assessment and the perils of Ofsted.

prefer it. A few years ago I rather lazily signed up for a tour along the upper reaches of the Amazon. I should have simply hired a boat and a guide and done it on my own. For one thing, since it was August, most of my companions turned out to be teachers from Britain. We cruised through the flooded forest, catching occasional glimpses of giant otters and river dolphins: it should have been magical. But being teachers (and, before anyone writes in, I used to be one myself) they found it impossible not to talk shop, so that our voyage was accompanied by non-stop discussion of Key Stage 3 assessment and the perils of Ofsted.

They also divided pretty neatly into three categories. There were the ones who couldn’t bear to see anything without demanding to know instantly what it was called. This doesn’t sound unreasonable, until you remember the sheer number of birds, beasts and beetles you get to see in the Amazon. When each appearance is greeted by a shouted demand for further information, it can become rather irritating. The second category was that of the manic photographer, who was forever getting cross because you were invading their airspace. The evil glances and the muttered “I’d have got that if you hadn’t moved just then,” became increasingly wearing. The most irritating group of all, however – and some people managed, by superhuman effort, to belong to all three – consisted of those who felt it their duty to supply a running commentary on everything we saw. “Ooh, it’s eating a frog. Look, it’s feeding its young. Look, it’s got a blue head. Look…” I know that David Attenborough had to start somewhere, but a couple of days of incessant commentary induced an almost psychotic fury.

So I don’t go with groups any more. I occasionally travel with picked companions, but you have to know each other pretty well. It’s not my snoring, which means that no one I share a room with gets a wink of sleep; or their inability to go anywhere until they’ve had breakfast, meaning that you set off hours after you should have done – because presumably you knew about these little weaknesses before you ever left home. It’s all those things you only discover when you’ve got wherever it is you’re going. They can’t sleep in a hut because it might contain spiders. You spend hours in markets haggling over fetish dolls and anklets made of beetle wing-cases. They can’t move at more than two miles an hour because they’re adding birds to their life-list. And so on. Easier, in short, to travel alone.

And what’s the scariest experience I’ve ever had? That, I’m afraid, is another story for another day.

Nicolas Kinloch was born in Oxford and, until his retirement last year, was a history teacher. He has been – amongst other things – deputy president of the Historical Association and an honorary member of the Bade people of northern Nigeria. He lives in Cambridge, and divides his time between writing history books and travelling to remote places.

Remote Places 1 2