At home with the Romans: The artefacts

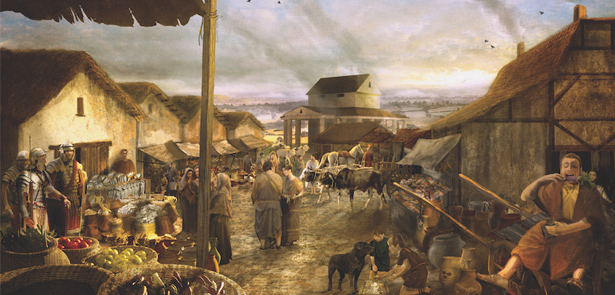

Peterborough Museum’s Roman Gallery has undergone refurbishment as part of the Romans Revisited Project, featuring entirely new displays and huge CG images recreating the Roman period

This exciting project has been funded and supported by Arts Council England, and led by Vivacity Heritage, with the support of local organisations and land owners, including Nene Park Trust and St Kyneburgha of Castor. The project aims to develop a centre of excellence for the East of England in Peterborough for the interpretation of our Roman Heritage across multiple sites. It creates a link between the objects on display at Peterborough Museum and the places where they were found, connecting people with the rich heritage on their doorsteps. The project has also enabled a re-invigoration of the displays and interpretation at Peterborough Museum in light of new archaeological evidence.

Here, Professor Stephen Upex, consultant archaeologist on the project, selects the artefacts from Peterborough Museum’s collection, which most intrigue him…

IX Legion tile

IX Legion tile

‘I’ve been looking at this since I was about 10… It’s significant because it tells us about the military situation in the area. Longthorpe fortress, a 27 acre fortress on the outskirts of Peterborough, found in the 60s by air photography, and excavated by Sheppard Frere and John St Joseph – is the base for a real chunk of British, Roman history. The Ninth Legion are there, and when Boudicca attacks the Roman legions in the AD60s, in the Boudiccan revolt, the Roman writer Tacitus tells us that troops from a base – he doesn’t name it – head off southwards to try to prevent the Britons from causing havoc in Essex and setting fire to London, which ultimately Boudicca’s army did. So, the commander at Longthorpe takes his cavalry unit and probably some infantry as well, down to meet Boudicca. Tacitus is writing in about the year 120AD, in southern France, but he had clear indications from a relative who was with the invasion force, and he says that the Romans brought Boudicca into the field of battle – and Boudicca annihilated them. His very words were: ‘the Roman troops limped back to their base’. For a Roman writer to admit that they were so heavily defeated implies they really were pretty badly mauled. And when you look at the fortress, 27 acres of the first phase is reduced down to a much smaller fort inside the original fort walls. Simply put, it must be that the troops who had ‘limped back’ could no longer man the entire defensive circuit. So we’ve got a classical writer telling us about a fort, and the Ninth Hispanic Legion – Legio IX Hispana – who we know were here, because this tile tells us exactly that: it has ‘HISP IX’ on it. Archaeology is all about jigsaw pieces, and the bigger the piece, the more of the picture you’ve got – and this is a very significant jigsaw piece! A fabulous object, which tells us a lot about Peterborough.’

Mortarium fragment

Mortarium fragment

‘Another great object from the museum collection… This is part of a large mortarium. The vessel is rough inside, so you’d put pulses or wheat or something inside, then pound it up with a pestle, and this is the spout for pouring the stuff out. There are several great things about this object. One is that it has the name of the potter himself: Sennianus. It’s then got the name of the Roman town, Durobrivis – with ‘vrit’ at the end meaning ‘fired this’. So, all together SENNIANUS DUROBRIVIS VRIT means “Sennianus fired me at Durobrivae”. You can’t get any better than that for linking those pieces of the jigsaw together. The potter was probably local, and perhaps this was a way of advertising his wares – but it also gives us the name of the town, and that tells us an awful lot. This is 2nd century, so it’s clearly already of some importance by then. This is actually the very first time we hear the name “Durobrivae” recorded anywhere, so it’s a very significant piece of pottery.’

Hunt cup

Hunt cup

‘This is a hunt cup from the Water Newton and Castor area. This stuff is called Castor ware, or Nene Valley ware. It’s got a hare on it – not a rabbit – and around the other side it’s being chased by a dog. Hares are here in the Roman period, and in the Celtic period have deity-like status; rabbits don’t appear in the record until the Norman period, as they’re not native. But it’s a typical hunting scene, hence the name. These figures are what’s called appliqué – little models of the dogs and hares that are sculpted separately and stuck on. These are made locally in the 2nd-3rd centuries, and it’s a colour coated vessel, which means it’s fired in the kiln, and then the potter dips it into a bucket of slip with minerals in it to give it the colour. He holds it around the base as he does that, and you can see his fingerprints there. He then stands it back on the shelf of the kiln and fires it. A lovely object – one of the great pots of the museum collection.’

Water Newton silver

Water Newton silver

‘This is one of a range of silver objects that was originally found in the Roman town. The originals are in the British Museum, because they are so significant, but these are remarkably good reproductions. It comes with other objects – several of silver, and one of gold – and only when you put them all together do you realise what they are. These are actually the most internationally significant Christian silver objects from the Empire – the very first time that we see anywhere in the world what might be called in the medieval period “communion plate”. There is a vessel that one might suspect is a chalice, a wine bottle, spoons, plates, and little metal plaques. Early Christians in Durobrivae were probably setting up a church, and benefacting or giving objects like this to the church, for use in the building. This bowl is wonderful, because it has the names of the people who benefacted the object around the outside. One vessel from the hoard is given by a man called Publianus, and the inscription says: “I, Publianus dedicate this to your altar, O Lord”, meaning he is giving the vessel to the altar. The word ‘altar’ is quite difficult to interpret in Latin. It could be just that – a stone altar – but equally it could mean a church or building. That is the great thing about the object, because it suggests there could be church in Durobrivae in the 3rd-4th centuries. It’s a fabulous collection of objects, that really puts Peterborough on the map, internationally.’

Lead font

Lead font

‘This comes from a large-scale excavation at Ashton, near Oundle, undertaken in 1976 by John Hadman and myself, in advance of the Oundle bypass. When we found this, it was actually trapped 18 feet down in a 32 foot deep well, and it took about five days to work out how to get it out! We had to get electricity, air and a water pump down there. And it was all squashed in. It has a chirho – a Christian symbol [which looks like a “P” and an “X” superimposed] – on the side, and someone had stamped on that, and then chucked it down the well so no one could use it. Presumably it’s pagans doing this. This happened some time in the late 3rd-4th century. At that time, Christianity was sometimes in fashion, but sometimes not – it’s not until you get Emperor Constantine the Great around 300AD that it becomes the state religion. Before that, some emperors allowed it, some didn’t. It’s what you might call a “portafont”… If you look at the sides its got lugs on it where you could put two poles through and have four blokes lift it onto a cart, to take it around. It’s the period when Christianity is just beginning. We know precious little about it, but there’s probably a church developing at Castor, hence the Water Newton silver. We assume that somebody was going around and converting people in outlying villages so you’d have stood in it and had water poured over you. Whether all those people went willingly, we may never know.

The new Roman gallery opens to the public on 15 November 2014.

To find out more about the museum, its collections and special heritage talks and events, visit www.vivacity-peterborough.com