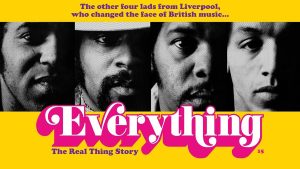

The Real Thing

They’ve got connections to The Beatles, they worked with Michael Jackson and Jeff Wayne, they were the first Black group to have a number 1 in the UK, and they’ve been described as one of the most important bands in the history of British music. Now they’re coming to town and will be performing their greatest hits like You to Me Are Everything and Can’t Get by Without You to promote their first new album in 40 years. We sat down with frontman Chris Amoo to get the real story about The Real Thing.

Your brother Eddie’s band, The Chants, was famously backed by The Beatles in the Cavern. Were you performing at that point?

No, Eddie was eight years older than me, so I was too young. But I did meet Paul McCartney a couple of times and he was lovely. When The Real Thing was voted best new group of 1976, Paul won an award with Wings, and he was absolutely over the moon to see us there. He said “It’s great to see you guys from Liverpool doing so well. Keep doing it! Keep doing it!”.

How bad was racism on the streets of Liverpool in the 1970s?

I was too young in the early ‘70s to really notice it. But, in them days, we had our own area of Liverpool, which was Toxteth, so it was very cocooned. Everybody knew each other, and we had our own clubs, our own pubs – everything we needed. We were too young to realise that there was a world outside of Toxteth where we weren’t welcome. But in Toxteth, there was such a great sense of warmth and community. It was fantastic. And, because everyone knew you, you couldn’t misbehave, or someone would shout “I’m going to tell your mother!”. It was a very safe place to be, but once you got outside of the area, that’s when you realised that things weren’t quite what they seemed.

You worked for Jeff Wayne of War of the Worlds fame in the early days. How did that come about?

By 1974 we had won Opportunity Knocks, so we were quite well known. Jeff Wayne was looking for vocalists to sing jingles for adverts, so our manager introduced us, and we started working with him. We did TV jingles for things like Wrigley’s Spearmint Gum, and that’s what was keeping us alive at that point because, without that money coming in, we’d have had nothing.

And you say you owe a debt of gratitude to David Essex. How much did he help and encourage you as a band?

And you say you owe a debt of gratitude to David Essex. How much did he help and encourage you as a band?

He helped us in every way you could imagine. Jeff Wayne was producing David’s album and he asked us to come in and do some vocals. David loved us, because we were just four guys from Toxteth, and he was a working-class lad from the East End of London. He could see that we were writing our own songs and weren’t trying to be American, and he loved that. He took us out on tour with him and introduced us to his audience. We would go on and perform as The Real Thing and then, when David came on, we’d do backing-vocals for him too. But what I really loved about David was that he always encouraged us to be ourselves.

You to Me Are Everything was the first UK number 1 by a Black band. Were you aware of that at the time, and how much did it mean to you that you were breaking down doors for other Black artists?

We didn’t think anything about that at all, in all honesty. It didn’t even cross our minds. When we thought of other artists at the time, we thought of Black American artists. All the Black British groups that were around at the time were just friends of ours and regular guys, just like us. So, we didn’t think we were breaking down any barriers. But it’s only when you look back on history that you realise you were breaking down barriers. I had no idea at the time that we were the first Black band to have a number 1 in the UK.

You had so much success so quickly after coming from such a humble background in Toxteth. Was that hard to adjust to?

No, not at all – it was easy to get used to having a bit more money! And getting recognised, getting media attention, and getting chased by girls was all part and parcel of it. That’s why you get into the business in the first place! It’s a lovely, lovely feeling, providing you’ve got someone behind you who can keep your feet on the ground. Our manager, Tony Hall, said “Look guys, you’re having a great time, but these things come and go, so don’t take anything for granted. Enjoy it but look after what you’ve got.”. He had seen it all before.

You worked with The Jacksons too. What was that like?

Yes, we played with The Jacksons at The Rainbow Theatre in London. We were supporting them, but we weren’t allowed to go anywhere near them, which was very disappointing. They were up their own a***s really. The whole thing was disappointing, because they weren’t as good live as I thought they were going to be either.

Were you surprised by your revival in the 1980s when your biggest hits were remixed and re-released?

Were you surprised by your revival in the 1980s when your biggest hits were remixed and re-released?

We couldn’t believe it! It was an amazing time. It was even more enjoyable than the first time ‘round in the ‘70s, because, by then, we realised how easy it was to lose it all. A DJ called Froggy remixed You to Me Are Everything and that’s when people realised it was a timeless classic.

And then there was the controversy over you playing Sun City in 1983 with David Essex at the height of apartheid. Is that something you regret?

Yes. We weren’t aware of all the facts at the time. We thought we were going to a place where it was okay for anyone to go to the gig. We were staying in the richest part of Sun City, where all the casinos were, and there were no other Black people at all. The concert was open to Black people, but they couldn’t afford to go. So, it was all a big show – a big PR exercise. But I’m glad I experienced it and saw it for what it really was. And outside of the Sun City resort, I couldn’t believe the squalor people were living in. That was my first experience of anything remotely like that. It was so, so sad.

Have you toured constantly since the ‘70s?

Yes. There’s never been a time since the early 1970s that we haven’t been on tour. So, that’s 50 years of constant touring! It’s incredible that you can do something for that long and still enjoy it as much. You couldn’t do it if you didn’t enjoy it.

You lost band member Ray Lake in 2000 after a history of mental health issues and drug abuse. How hard was that for you?

It was very difficult for us to see him losing his way. He had a terrible childhood, and it took a lot to keep him in check – and I don’t like to say that about another adult, but that was basically what we had to do. It worked for a long time, but you can’t control somebody when you’re not with them, so when he wasn’t with the band, that’s when it all went wrong for him.

And you sadly lost your big brother and fellow band member Eddie in 2018. Did you ever think of stopping with the band, or was that never an option?

It was always an option and we seriously considered it. But me and Dave Smith love the business so much so we agreed that, if we could make it work with just the two of us on vocals, we could carry on. We decided we weren’t going to bring anyone else into the group. That was the most important decision. By the time Eddie passed away, everyone was used to The Real Thing being three vocalists, but me and Dave felt that, if we brought someone else in, it definitely wouldn’t be The Real Thing anymore. Me and Dave have been singing together since we were 14, so the dynamic would change too much, and so would the sound. So, we just had to work out a way of making it work with just the two of us. I now record Eddie’s falsetto parts on tape, and we have those backing us on stage and it works really well.

You’ve been described as one of the most important bands in the history of British music. Are you getting more recognition now for the barriers you broke down in the ‘70s?

Absolutely. I felt that, until recently, The Real Thing had been written out of any histories of British music – especially Black music. We never got a mention, but that all changed when the film (Everything: The Real Thing Story) came out in 2019. Suddenly, lots of people came out of the woodwork and said we were so important. I thought “That’s nice, but why didn’t you say that when Eddie was still alive?”. He would have been really proud to hear that.

You’ve inspired so many bands and there have been covers of your work by various artists, including Mary J Blige, Philip Bailey, and Courtney Pine. How gratifying is that?

You’ve inspired so many bands and there have been covers of your work by various artists, including Mary J Blige, Philip Bailey, and Courtney Pine. How gratifying is that?

It feels fantastic because those are all people who we tremendously respect. When we saw that Spike Lee had used our song Children of the Ghetto in his film Clockers, it was amazing.

And do you enjoy performing live now more than ever?

We enjoy performing live more than any other aspect of the music industry. If somebody said to us “You’ll never make a record and you’ll never be on TV or anything like that, but you can work live”, we would settle for that. And we still do.

THE REAL THING WILL BE PERFORMING AT THE CRESSET ON SUNDAY 11 SEPTEMBER. TICKETS COST £29.50. TO BOOK VISIT CRESSET.CO.UK OR CALL THE BOX OFFICE ON 01733 265705.

Words: Stuart Barker