Countryside Regeneration – When the community’s in charge!

A quarter of a century ago, local residents joined together to save a particular heritage site from years of misuse, which had caused widespread wildlife depletion. Since then, the Langdyke Countryside Trust has continued on its mission to help nature thrive in the fields, meadows, waterways and woodlands to the west of Peterborough. The Moment takes a look at how local people championed change and, together, created a rural idyll.

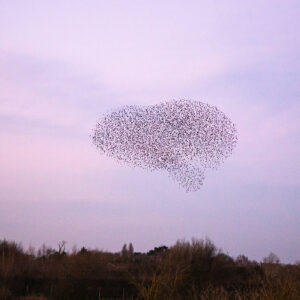

As residents of Peterborough and its surrounding areas, have you experienced the beauty of the countryside to the west of the city? Have you had the chance to see hares racing across the meadows? Or heard the sharp cries of swifts swirling over village rooftops? What about merely sitting in the late evening light, watching the sun disappear beneath the field furrows?

As residents of Peterborough and its surrounding areas, have you experienced the beauty of the countryside to the west of the city? Have you had the chance to see hares racing across the meadows? Or heard the sharp cries of swifts swirling over village rooftops? What about merely sitting in the late evening light, watching the sun disappear beneath the field furrows?

The countryside between Peterborough and Stamford often feels a little undiscovered. Yet, once people come across its charms they’re amazed at the sheer diversity of wildlife and habitats. It’s magical. As an example, residents and visitors can enjoy woodland walks at Castor Hanglands or stroll along the banks of the River Nene. Or they might choose to visit local nature reserves such as Barnack Hills and Holes.

But this landscape – once home to the poet John Clare – and its accompanying wildlife, has been under threat from the loss of natural habitat and the increasing impact of climate change for some time. The list of species in steep decline is long. Iconic rural birds such as the cuckoo and the turtle dove have disappeared from many areas. Hedgehogs and brown hares are now rarely seen, while 80% of butterflies in the UK have declined since the 1970s.

However, in this little corner of land to the west of Peterborough, something unusual has happened to try and reverse these changes. Here, the local community has pulled together to reduce the threat of nature depletion. Residents are working alongside landowners and farmers to champion nature, standing together to protect it for future generations.

Creating community action

Creating community action

The Langdyke Countryside Trust was founded 25 years ago to try and stop nature depletion in its tracks. Everyone involved in the project has dedicated their time for free to conserve and boost the natural and built heritage in the area. It’s a rare experiment, but one that’s seen results.

Richard Astle, Chair of the Langdyke Countryside Trust, says: ‘At the heart of Langdyke is that sense of local pride and people just being really interested in the countryside around them. And I don’t think that’s changed at all over the years. You know, we work across the area between Peterborough and Stamford, and it’s all about people taking action for their nearby spaces.’

The charity’s forward momentum has been extraordinary. Now managing eight local nature areas, and on the verge of acquiring a ninth, the Trust’s aim is simple: to stand up for nature, heritage and local communities.

Back in 1999, four local men got together with the specific intention of reversing decades of habitat and species loss. Alongside that was the aim of encouraging greater public awareness, access to nature, and local residents’ involvement with their closest countryside. However, it was to be another six years before the group managed to acquire its first nature reserve.

Wonderful wildlife habitats

Wonderful wildlife habitats

Swaddywell Pit, located south of Helpston, takes its name from a nearby spring where reputedly an ancient sword was once found. Over time ‘Swordy Well’ became Swaddywell. In medieval times, the quarry at Swaddywell may well have provided stone for many local churches and cathedrals. The site also has its place in literature, being the subject of two of John Clare’s poems. It was listed in Sir Charles Rothschild’s famous 1912 list of key places for nature across the country, and in 1915 it became one of the UK’s first nature reserves.

Fortunes changed, however, during the Second World War when the site was used as a bomb dump, and then later (in the 1980s) for landfill. In the 1990s the plot was turned into a Volkswagen racetrack, with accompanying festivals and fireworks displays. But when development plans were thwarted by local opposition, the Langdyke Countryside Trust stepped in to take over the site. After many years of negotiation, they succeeded in buying the rather barren and waste-strewn location in 2003.

‘The Langdyke Trust was formed with the specific purpose of trying to channel all that negative energy of people’s opposition into something more positive, where they actually took on the site to create something,’ says Richard. ‘It’s a real community asset, and an asset for nature too.’

Today Swaddywell is once again well-loved. Every week a team of volunteers gather on the reserve and – together with its resident flock of Hebridean sheep – manage the site. The landscape shows markers of its chequered past, but the man- made wounds have been lessened by nature. It’s no longer a waste ground but is instead home to eight species of orchid and over 1,200 species of invertebrate. The quarry is alive with 14 varieties of dragonfly and large numbers of swallows, house martins and swifts, who fly up from their nests in the nearby villages to feed over the ponds in summer.

Swaddywell is testament to the power of a community to restore biodiversity and heal a land. The regeneration project proved the Trust’s ability to take damaged and depleted landscapes and breathe new life back into them.

After gaining the first reserve, the Trust’s plans and fundraising efforts accelerated. In 2009 the next acquisition was Torpel Manor Field at the end of West Street, Helpston. When the site was taken over, it had been grazed by horses for many years and the only buildings were a cluster of leaking stables and a large pylon. Work started immediately to unlock the secrets of this historic site, which has Ancient Monument status and is the location of a Norman manor house and medieval hamlet. The story of Torpel has now been brought to life via a Heritage Lottery Fund project, which involved creating a visitor centre and facilities for schools. The Trust’s History and Archaeology Group has also worked to restore sections of the medieval stone wall, which encircles the field.

After gaining the first reserve, the Trust’s plans and fundraising efforts accelerated. In 2009 the next acquisition was Torpel Manor Field at the end of West Street, Helpston. When the site was taken over, it had been grazed by horses for many years and the only buildings were a cluster of leaking stables and a large pylon. Work started immediately to unlock the secrets of this historic site, which has Ancient Monument status and is the location of a Norman manor house and medieval hamlet. The story of Torpel has now been brought to life via a Heritage Lottery Fund project, which involved creating a visitor centre and facilities for schools. The Trust’s History and Archaeology Group has also worked to restore sections of the medieval stone wall, which encircles the field.

20-acre Bainton Heath became the Trust’s third reserve, this time in partnership with National Grid. The site was a former tip for waste fly ash from power stations in the north of England, but has since been colonised by a fascinating variety of flowers, mosses, lichens, insects and birds. Nightingales still sing here, and it also hosts breeding populations of summer migrants;

such as chiffchaff, whitethroat, lesser whitethroat, and willow, sedge, reed and grasshopper warblers.

In the same year (2009) Langdyke entered into a management agreement with Tarmac to look after part of the restored gravel pits between Etton and Maxey, north of the Maxey Cut. The fabulous 90-acre mosaic of reed, open water and woodland at Etton- Maxey Pits is where wetland birds have returned to breed. Water voles have made their homes here too and pyramidal orchids have spread across the site in their thousands.

Ambition not yet satisfied, Etton High Meadow was established as the Trust’s fifth reserve. The site consists of a barn, a series of paddocks, a community orchard, allotments for local residents, and more than 70 heritage fruit trees. The Trust’s vision is that High Meadow will become a treasured asset for local communities: providing access to locally grown fruit, a venue for community events and a destination on Peterborough’s Green Wheel.

Ambition not yet satisfied, Etton High Meadow was established as the Trust’s fifth reserve. The site consists of a barn, a series of paddocks, a community orchard, allotments for local residents, and more than 70 heritage fruit trees. The Trust’s vision is that High Meadow will become a treasured asset for local communities: providing access to locally grown fruit, a venue for community events and a destination on Peterborough’s Green Wheel.

The sixth reserve, Vergette Wood Meadow, is the one Richard describes as his favourite. It’s a small parcel of land and water that is a haven for wildflowers, dragonflies and ducks. ‘It’s completely man-made, because it emanates from the gravel pits and the restoration after,’ says Richard. ‘It’s a great example of how man- made activity can be turned back into something wonderful for nature. It’s just this glorious wildflower meadow, which in summer is brimming full of colour.”

Lastly, there’s Marholm Field Bank – a tiny wildflower area running alongside the A47 – and ancient M’Lady’s Pond near Ailsworth.

Nature at the heart of our lives

These reserves help to pull together a patchwork of habitats that benefit local people and wildlife. Richard explains: ‘It’s astonishing how many different things you can see on the same day in this area. You could be watching otters in the river, or seeing butterflies in the woodland, and all kinds of rare orchids. So whatever it is you’re interested in, whether it’s mammals or insects or birds, there’s something to see at all times of the year.’

Here, to the west of Peterborough, residents decided that they valued living in an area where nature is at the heart of their lives. Where bees, insects, birds and other wildlife thrive. Where there are ponds, meadows, wildflowers, hedgerows and trees. And where local people can walk or cycle, simply enjoying the sights and sounds of the natural world.

Here, to the west of Peterborough, residents decided that they valued living in an area where nature is at the heart of their lives. Where bees, insects, birds and other wildlife thrive. Where there are ponds, meadows, wildflowers, hedgerows and trees. And where local people can walk or cycle, simply enjoying the sights and sounds of the natural world.

Today Langdyke has a dedicated core of regular volunteers. Around 210 local households are members, paying an annual subscription to raise funds for managing and improving the reserves. Malcolm Holley, who has been volunteering for a number of years, says: ‘I feel a real sense of achievement when I have spent time out on the reserves. It helps keep me fit and healthy and there’s a great team spirit among the volunteers.’

As well as a wide-ranging events programme throughout the year, which enables access to many of the reserves, the Trust has also set up a team of Artists in Residence to carry out wide-ranging projects and to boost the link between arts and the environment.

When asked what the future holds for the Trust, Richard answers: ‘We want to carry out more of the same. I think the really big thing for us is working even more closely with farmers and landowners and looking to recreate habitats across the area: more woodlands and wetlands and grasslands. At the same time, we don’t want to lose sight of the really simple stuff, such as working with local people to put up nest boxes or planting hedges.’

The work of residents has made such a difference to these local places, people, and of course to wildlife too. The essence of the community project has been to take areas of land that have been subject to prolonged neglect, and then to encourage nature to reclaim them. This has been for the benefit of all species – including people.

As Richard says, ‘To me, it’s a story about communities taking control, when many people perhaps feel they can’t make a difference and that it’s out of their hands, particularly when it comes to climate change and biodiversity. This is an example where a local community has taken action, is still taking action, and we’re seeing the results of that.’

Do you want to get involved?

- Email to find out about volunteering.

- Visit www.langdyke.org.uk to see more about the Trust and its activities.

- The Langdyke Countryside Trust’s next general meeting will be held on the 18th July 2024. Members and non-members are very welcome to attend.