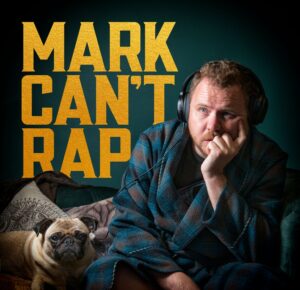

Mark Grist | Mark Can’t Rap

Mark Grist is an award-winning poet, educator and former Peterborough English teacher who shot to national fame in 2011 when his win against MC Blizzard in a Don’t Flop rap battle went viral. It has become the most viewed UK vs UK rap battle of all time, with 5.5 million views to date. In 2019 he created a podcast called Mark Can’t Rap, the first season of which ended with him making a rap mixtape. Season two upped the game, with even bigger name guests and the aim of making a full album. Then COVID hit, tours were cancelled, and the podcast took on a whole new significance… Half way through season two, Toby Venables talked to him.

The podcast has been going for a while now – but what sparked it off in the first place?

When I started rap battling, my rap battle with Blizzard became the most viewed UK versus UK rap battle ever. It became a big news item. And that was cool, but what I found very difficult was that I couldn’t really explain what I was doing. I didn’t have control of the narrative. It was spat out in the press and everything; everyone else was making up these stories – some were maybe quite racist, and also quite anti-teenager – and were putting out there that I was teaching these guys a lesson. But I wasn’t really. I was there to learn from these guys. And there was another thing… As a teacher, I was finding that young people who were really creative and passionate about words often hated English lessons. And within English classrooms – at least, as far as the curriculum is concerned – we acted as though that passion for writing creatively in rap is worth nothing.

In the English classroom, if anything, it’s considered the wrong way of using language. And I didn’t understand how this could be the case. I thought, as an English teacher, I have a choice here. I can either say to them ‘I don’t understand rap, teach me about it, I want to learn about it’ or I can go ‘Well, I don’t understand rap, and it’s worthless and meaningless and I don’t want to know about it…’. We have a system within education that expects knowledge to be passed from a teacher to a student in a way that suggests the teacher is an authority, and we struggle sometimes as teachers with accepting that we don’t know things and we could do with learning things. But that’s essentially why I was rap battling – to learn.

In spite of that, a lot of people who saw the rap battling were like ‘Yeah, this teacher is teaching these young people and these MCs about the importance of English language’. To be honest, I was often saying more offensive things in these rap battles than my opponents were, but because I’m in a suit and they’re wearing a baseball cap, the vibe is somehow ‘cocky teenagers destroyed by eloquent teacher’. We have this assumption that there are right and wrong ways to use language, and the teacher is the gatekeeper for what is right and wrong; but I think that’s not very healthy, especially when you look at the A-level statistics showing how many students are ditching English as soon as they get the chance. They don’t feel it speaks to them. And I was like ‘What am I going to do about this?’. Because I’ve gone and rap battled, and this feeling we have about it is so prevalent that it’s shaping how everyone responds to my rap battles, thinking that I’m teaching these guys a lesson. So I stepped back from it and thought, ‘I want to explore it in a way where I can control the story’.

And a podcast is a great way to do that. In a podcast, I can talk to people directly and I can explain what I’m doing. It’s not going to be as viral and visually as exciting, but it means I could start from a perspective of learning about this, and being low status. And the title Mark Can’t Rap made sense, because I was at that starting point. That’s how I want this dynamic to be, and I wanted an audience to understand that it’s OK for a teacher to say ‘I can’t do something and I want to learn about it’.

What was the response like?

The main thing people keep saying to me is ‘But you can rap!’ And, OK, I’m getting better… When I started out in episode one I flew to Mexico, and I rapped in front of the Global Head of Music Innovation at Red Bull.

He said he would give me five minutes of his time to rap to him. I knew I probably wouldn’t get a record deal, but in the back of your head, you’re like ‘Rah!’. But yeah, I was terrible. And I was told, categorically, ‘You can’t rap’ by someone whose job within this industry is to spot people who can and can’t rap. He actually said it sounded like there was something wrong with me! And so at that point, you’re like, OK, cool. So we’ve shown where I am. Now, let’s see if we can prove by the end of a series that I can get better. At least we can show that it’s a craft and we should take it seriously, and hear from MCs along the way.

Are there common misconceptions about what rap is?

Often we assume that it’s this kind of posturing, braggadocious, hyper-masculine thing – these guys being very aggressive and intimidating and puffing out their chests. But what’s been really lovely about going in and speaking to rappers and saying ‘I don’t understand this thing – can you teach me about it?’ is that I found so much compassion and warmth. It’s been so welcoming – much more welcoming, I think, than the poetry world can be for MCs who move into poetry. And for an English teacher who’s passionate about language, it’s incredible hearing these really intelligent, articulate individuals, many of whom did not achieve a passing grade in English at GCSE. It’s jaw-dropping how much they understand, and how much they can teach me, and how rich and exciting their language is – and how my engagement with language has been improved by this.

Did the podcast have a goal?

The first season was seven episodes, and the goal was ‘Could I make a mixtape at the end of seven episodes?’ I did. I put it out on Spotify and everything. And it’s pretty good.

It’s not great. So, with the second series, it was ‘Can I make an album?’ That was going to be the idea. And then COVID hit. And I was locked inside, not sure what to do. The idea of making an album seemed almost impossible. And then I got to thinking about it. One of the great things about rap is ‘sharing the views the news won’t tell youse’; it’s a mirrored surface that reflects the environment and the world. I think that’s why it’s so relevant and so powerful, and why rappers are considered the most influential – certainly the most financially successful – types of writers that exist. You know, Kanye West goes and meets with the President of the USA. That’s a big deal. So, it seemed to make sense that in the second series, I would just document what’s going on in the UK in relation to the pandemic; I would see if I could learn lessons from rap and from rappers about overcoming difficulty, being positive and creative, and trying to find a way to make something of your situation, no matter how difficult it seems.

You’ve had some amazing contributors…

Yes! We had Ghostface Killah in episode two, who gave me a proper pep talk – ‘Are you going to fold? Or are you going to keep on going?’. We’ve had Charlie Tuna from Jurassic 5 come on and explain what rap has meant to him, and how it’s helped him understand who he is within the world – and how to be a positive individual within society through rapping. Lunar C is appearing next week, which is going to be super cool. He’s fantastic. And right now I’m trying to get Ice-T to do a bit for one of the episodes. At the same time I’ve spoken with MCs about conspiracy theory, and how some MCs don’t trust the vaccination programme. I’ve learned how to listen to people and have reasonable, polite disagreements within that environment, which I think could be useful for a lot of us right now, when we’re not really agreeing and everything is so polarised. So that’s what the second series is really about. It’s delved into all the changes in our lives in the last year and a half – the moment that, you know, Scotch Egg was classified as a meal, or how pubs were safe to meet in but our homes weren’t, or the moment that two metres became one metre plus – all these changes to our lives which caused a huge amount of fallout.

What shape does a typical episode take?

There are interviews, but there’s always a quest or a journey through each episode. The idea is you don’t have to know anything about rap – in fact, if you know nothing about rap you might even get more from it. It’s really just about following someone who’s struggling and stuck, and hoping to learn more about how to survive and navigate the pandemic.

And, yeah, that’s it. So we’ve got all these interviews, and we kind-of go through these things. I produce work over the course of the series and I share my rapping. The idea is that if I share my failures, I think that’s helpful. For someone to explain they struggle with things. And I think a lot of people enjoy the podcast because the process I go through is useful for any kind of writing – and not just writing, but how to be creative. And we’ve got music videos dropping. The new music video is pretty mad. I don’t know about anyone else, but while we were all kind-of freaking out about COVID being the biggest thing since the war, I was just soaking up nostalgic TV and films – stuff that just made me feel comforted from my childhood. And I wrote this whole rap about 150 baddies from TV, films and computer games, and that’s just gone online.

What do you find exciting about rap?

It’s an incredibly aspirational form of writing. It’s partly about showing off, doing what you can to be better with your words, to try and create the most complex, interesting, rich-sounding stuff. And there are so many techniques being used: assonance, multisyllabic rhymes – some MCs are using internal rhymes to such a high degree, and even rhyming entire sentences. That’s all incredibly exciting for someone who’s passionate about language.

What, ultimately, do you hope this achieves?

One of the reasons I wrote the podcast is because I’ve met a lot of teachers in my time who think

rap is dumb. That it’s meaningless bringing rap into the classroom. That it’s a cultural black hole – which I think is an interesting choice of words… But I’ve only ever been told those things by teachers who don’t listen to rap and don’t understand what’s going on. If I could achieve one thing with the podcast, I think it would just be to try and nudge a few teachers towards being open to learning new things, and accepting there’s value in things that we don’t understand.

I’m not saying we have to put rap on the curriculum at GCSE, but I do think we shouldn’t be afraid of having conversations about what we are teaching and what we’re missing out. I want the podcasts to at least show those people that rap is categorically not simpler and easier than other kinds of poetry and forms of writing. Certainly, I find rap really hard; that’s why it’s called Mark Can’t Rap and why it’s about me sharing my process. And if they can hear and understand that it is hard, then maybe those young people that are so dispirited by their English classrooms would feel a little bit more welcome. And I hope I get better. But the jury’s still out on that one…